SO MUCH FOR THAT —

Most scientists now reject the idea that the first Americans came by land

Researchers embrace the kelp highway hypothesis in “a dramatic intellectual turnabout.”

It's been one of the most contentious debates in anthropology, and now scientists are saying it's pretty much over. A group of prominent anthropologists have done an overview of the scientific literature and declare in Science magazine that the "Clovis first" hypothesis of the peopling of the Americas is dead.

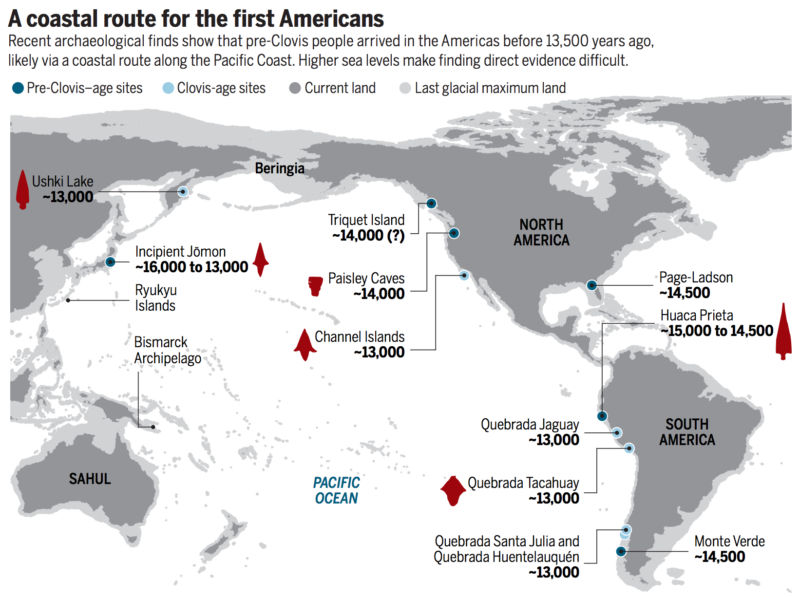

For decades, students were taught that the first people in the Americas were a group called the Clovis who walked over the Bering land bridge about 13,500 years ago. They arrived (so the narrative goes) via an ice-free corridor between glaciers in North America. But evidence has been piling up since the 1980s of human campsites in North and South America that date back much earlier than 13,500 years. At sites ranging from Oregon in the US to Monte Verde in Chile, evidence of human habitation goes back as far as 18,000 years.

In the 2000s, overwhelming evidence suggested that a pre-Clovis group had come to the Americans before there was an ice-free passage connecting Beringia to the Americas. As Smithsonian anthropologist Torben C. Rick and his colleagues put it, "In a dramatic intellectual turnabout, most archaeologists and other scholars now believe that the earliest Americans followed Pacific Rim shorelines from northeast Asia to Beringia and the Americas."

Now scholars are supporting the "kelp highway hypothesis," which holds that people reached the Americas when glaciers withdrew from the coasts of the Pacific Northwest 17,000 years ago, creating "a possible dispersal corridor rich in aquatic and terrestrial resources." Humans were able to boat and hike into the Americas along the coast due to the food-rich ecosystem provided by coastal kelp forests, which attracted fish, crustaceans, and more.

No one disputes that the Clovis peoples came through Beringia and the ice free corridor. But the Clovis would have formed a second wave of immigrants to the continent.

Despite all the evidence for human habitation, ranging from tools and butchered animal bones to the remains of campfires, scientists are still uncertain who the pre-Clovis peoples were. We have many examples of Clovis technology, with characteristic shapes for projectile points made from bone and stone. But we have no recognizable pre-Clovis toolkit.

That may be about to change, however. The pre-Clovis people traveled along a now-drowned coastline, submerged after the last of the ice-age glaciers melted. New techniques in marine archaeology, ranging from ROVs to underwater lasers, are helping scientists explore ancient submerged villages. A team even turned up a 14,500-year-old campsite in Florida in a blackwater sinkhole last year. [Would these "campers" have travelled from Europe?]

Rick and his colleagues write that the big question now is when pre-Clovis people actually arrived in the Americas. They suggest the arrival could be as early as 20,000 years ago on the verdant kelp highway. Other researchers, however, say people could have arrived during a temperate period about 130,000 years ago. A recent paper in Naturedescribes what appear to be the 130,000-year-old butchered remains of mastodons in California, along with sharp stones used to deflesh the animals. There is plenty of skepticism in the scientific community about this discovery, but the evidence can't be ignored.

To the best of our knowledge, the kelp highway brought humans to the Americas. Using boats and fishing tools, humans made it all the way from Asia to the Americas, founding many coastal communities along the way. And now for the next debate: who were they, and when exactly did they arrive?

No comments:

Post a Comment